Making Connections: Space Exploration Advances Health Sciences Research

Guest post by Reagan Perry, North Carolina State University undergraduate student

Reagan Perry recently completed her first year at NC State University. She intends to major in biology and pursue a career in healthcare.

I began this semester with NC Space Grant looking for more experience with research. I was not sure what exactly Dr. Susan White, NC Space Grant’s director, would suggest. She brought up studying how spaceflight affects bone density and other related areas of human health. This idea sparked my interest – and we hit the ground running.

I started by using various databases through the NC State Library to find articles and papers on this topic. Because I had a similar experience last semester with Dr. White, I felt much more comfortable. My search eventually led me to focus on three main papers (referenced at end of this post) where I found strong background information and inspiration for later ventures.

The first paper I read gave me information on the differences between male and females before and after spaceflight. The researchers concluded that although females begin spaceflight with less bone density than males, there is no statistical significance in the difference in BMC – bone mineral content – between males and females after spaceflight.

I then moved on to a second paper that went into more detail about specific areas of the body during spaceflight. The researchers in this paper separated the body into four regions. They concluded that region four (lower limbs) experienced the most done density loss during spaceflights of 28 or more days. The other upper regions were either relatively unaffected or actually experienced an increase in density.

To finish up my background research, I turned to a third paper. While it backed up much of the information presented to me in the second paper – that there was more risk for bone density loss in load-bearing regions of the body – it also noted that recovery begins around six months post space flight.

These last papers left me with a lot of questions, so Dr. White suggested that I try to set up conversations with researchers in this area to hear about their experiences and expertise in the field. With the help of Jobi Cook, NC Space Grant’s associate director, and Dr. White, I set out to interview three experts, one of whom works in North Carolina.

I first interviewed Dr. Jeffrey Willey from Wake Forest University, who focuses on “preventing musculoskeletal toxicity from cancer treatment and spaceflight.” Dr. Willey was very encouraging to me about my interests in undergraduate research and attending medical school. He started his career as a physical therapist, but found that he enjoyed the research side of health care much more. This has led him to work in a lab with test subjects, like mice, to understand how spaceflight affects health.

The main thing Dr. Willey pointed out to me was the importance of using muscles and bone, even when in space. Even after surgery/injury on Earth, it is important to use your limbs so they don’t develop osteoarthritic conditions. He transfers this known fact on Earth to astronauts in space in order to help them stay in peak physical condition.

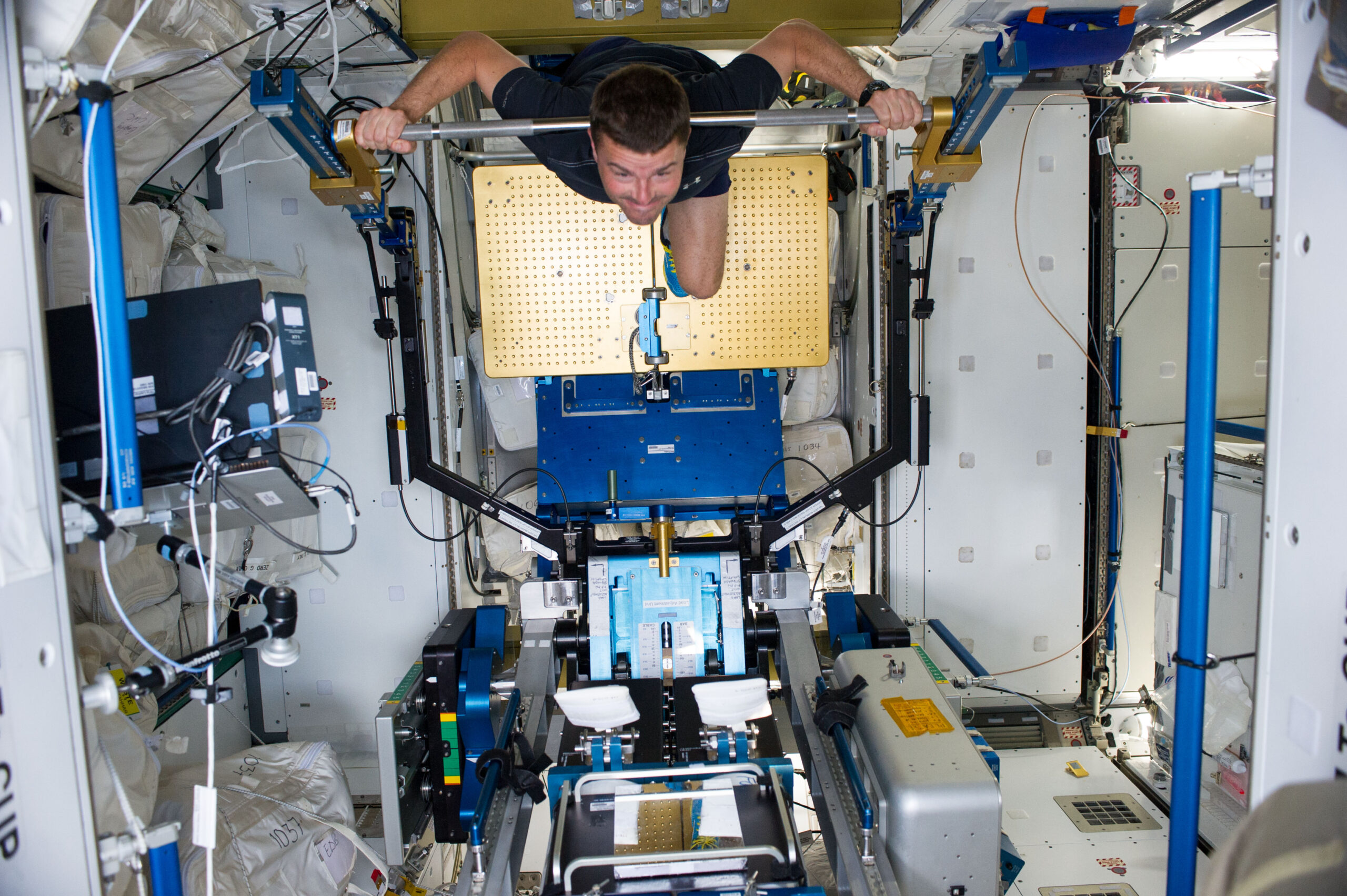

Next, I was very fortunate to talk with Dr. Liz Warren of NASA who works in operations for the International Space Station. She told me that at one point she considered going to medical school, too, but found research to be more of her strong suit. She recommended that I, and any other undergraduate, get involved in as much research as possible. Her time at NASA has involved improving bone health of astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS). She introduced me to the ARED (advanced resistive exercise device) that is on the ISS. She credits this machine with combating the issue of bone density loss in space.

Like Dr. Willey, Dr. Warren noted exercise and use are the best ways to combat bone density loss. Recently, Dr. Warren was a speaker at the 2021 Space Symposium with NC Space Grant. Events like these are a great way to learn from professional researchers and make connections for future mentors or research opportunities.

My last research conversation was with Dr. Craig Kundrot, the director of the Biological and Physical Sciences Division at NASA. I asked him how NASA was planning to combat bone density loss on the upcoming mission to Mars, because Dr. Warren mentioned that the ARED machine was too large to fit in the vessel that will go to Mars. He explained that although ARED is the best way to combat this issue, other machines – like an adapted stationary bike – can work as well.

Dr. Kundrot did note there were concerns that the bike would not be enough weight on the joints to maintain the same level of resistance to bone loss. Because bone density is hard to measure over short periods of time, Dr. Kundrot focuses on measuring indicators in the blood of astronauts to catch bone loss early. Dr. Kundrot also suggests summer internships at NASA to any undergraduate considering work with NASA in the future as a career.

I am incredibly grateful that these three accomplished researchers took time to speak with me. They all said the same thing: They love it when young students reach out with questions about research interests and careers.

This semester with NC Space Grant has taught me so much about research and making connections within my desired field of work. My next steps are undetermined, but I hope to complete hands-on research experiences in the future.

Are you an undergraduate student interested in connections between space explorations and various disciplines? NC Space Grant’s associate director, Jobi Cook, encourages you to connect with NC Space Grant for student opportunities like scholarships and internships.

Also, check out the American Society for Gravitational and Space Research, which has an active student chapter. The group regularly hosts webinars and other interactive forums for students to engage with the science community. The experts cited here are all active ASGSR members. The society’s next annual conference will take place in Baltimore, Maryland, Nov. 3-6, 2021. During the conference, students can take advantage of multiple networking events designed especially for them.

- Categories: